Publication

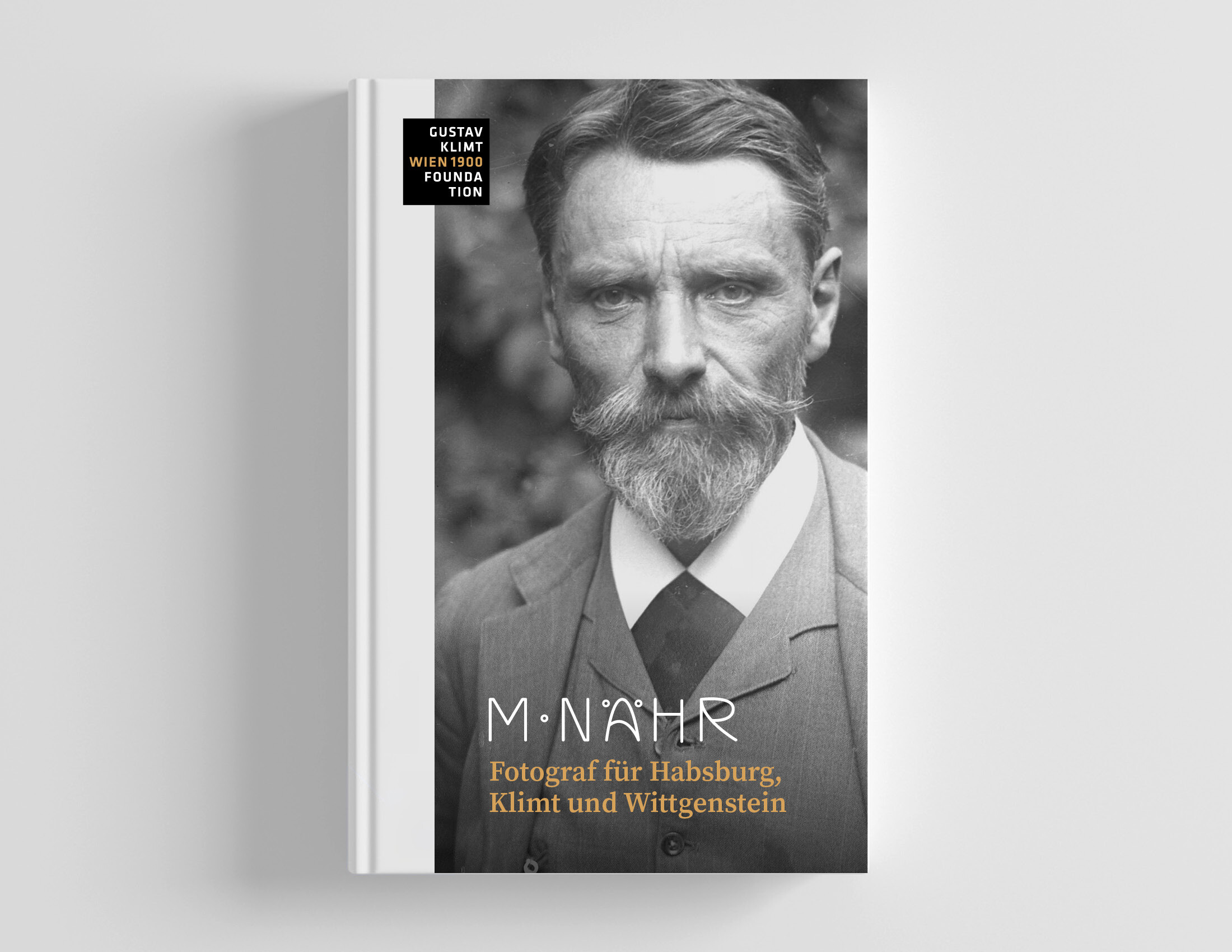

Moriz Nähr

Photographer for Habsburg, Klimt and Wittgenstein

Edited by Uwe Schögl, Sandra Tretter, Peter Weinhäupl for the Klimt Foundation

Publication date 2025

Intention

With glass negatives and original prints, the Klimt Foundation owns a significant part of Moriz Nähr’s estate, which in 2018 provided the impetus for the artist's first museum presentation at the Leopold Museum in Vienna. Together with the photo historian Uwe Schögl, the Klimt Foundation is publishing the first detailed monograph on Moriz Nähr in the series Edition Klimt-Research in 2025.

Contributions by well-known authors no longer perceive Nähr‘s oeuvre as a purely documentary phenomenon, but also contextualize the aesthetic and historical connections with Viennese Jugendstil and the work of Gustav Klimt.

Contents

The monograph attempts to cover all aspects of Moriz Nähr's work. In addition to longer essays, the publication also contains shorter essays and extensive photo series, which are divided into the following subject areas:

Biography

The life of the Viennese Modernist photographer is explored and described in detail.

Photographic and Artistic Work

The focus here is on Moriz Nähr's technique and visual language.

Landscapes - Urban Landscapes

Moriz Nähr's career developed from romantic landscape photography to capturing the disappearing old Vienna, in particular his neighborhood, the 7th district of Vienna.

Vienna Secession - Gustav Klimt - Art Nouveau

The exhibition traces Moriz Nähr's artistic career from his beginnings at the Hagengesellschaft to his work at the Secession, as well as his friendship with the painter Gustav Klimt.

House of Habsburg

As Archduke Franz Ferdinand's chamber photographer and Archduchess Isabella's photography teacher, Moriz Nähr had a great influence on the private and public image of the imperial houses, as will be shown here.

Wittgenstein and Moriz Nähr

The focus of this section is on the personal and professional relationship between Moriz Nähr and the Wittgensteins, with a particular emphasis on the famous composite portrait of the Wittgenstein siblings.

Portraits

Moriz Nähr not only captured Viennese celebrities in pictures, but was also portrayed by Joseph Rheden. These portraitists make it possible to reconstruct which camera Nähr himself used.

Teasers

Note: The following texts are abridged excerpts from two essays that are published in full in the monograph.

Andreas Gruber Objectively Viewed: The Moriz Nähr Portrait by Joseph Rheden

A portrait taken by the astronomer and photographer Joseph Rheden in 1940 shows Moriz Nähr at an advanced age taking a close look at an imposing, antique-looking lens.

It was intended for Rheden’s never published work Geistiges Österreich. Eine Sammlung mit Bildnissen aus dem österreichischen Kulturleben [Intellectual Austria. A Collection of Portraits from Austrian Cultural Life].[1] The fact that Rheden, like Nähr, liked to capture the considered personalities from science, art, and culture in their working environment seems to suggest that the picture was taken in Nähr’s apartment or studio.

Apart from this charming, yet rare insight into Nähr’s possible sphere of work, the picture raises the question of whether the subject might have taken photographs with this lens. In purely visual terms, it is an oversized version of a Petzval-type portrait lens. These lenses are generally characterized by a long construction and a large aperture.[2] They consist of two pairs of lenses; the front pair could usually be unscrewed and used separately for landscape photographs. This lens was the first whose construction was not based on empirical values; its optical composition had been calculated by the Viennese mathematician and physicist Joseph Petzval in 1840. It was originally put on the market by the Voigtländer company in 1841, but as no patent protection had been obtained, it was copied by many other firms in countless variations and sizes. Until the end of the nineteenth century, this very popular lens type could hold its own on the market under names like “Schnellarbeiter” (fast worker) for portrait photography and as a projection lens, because it boasted an enormous light intensity like no other lens type of that time. This was a decisive advantage in portrait photography, for which aberrations such as light fall-off, pronounced out-of-focus areas, and distortion at the edges were accepted.

May Moriz Nähr have worked with a lens of this size? This is absolutely possible, considering that such lenses were still in use in some renowned Viennese portrait studios around 1900.[3] However, as he—contrary to his landscape and architecture photographs usually captured on 21 × 27 cm glass negatives—exposed half-length portraits on negative plates measuring 16 × 12 cm to 21 × 16 cm at the most, he must have had a smaller portrait lens for portraits to hand, which did not allow the use of his standard large-format negatives.[4] The angle of vision was too small for architectural photographs. In addition, Nähr’s pictures do not reveal any significant distortions or similar aberrations as those mentioned above. This is why the probability that it is a standard lens used by Moriz Nähr is to be judged as low.

Further details can be made out in the background of the preserved original negatives of this portrait series,[5] which show a larger image area than the official print. We see the photographer turned to the right in three-quarter view, sitting in a chair with riveted backrest. His right arm rests on a desk on which books and magazines are stacked. The shelves of a massive library cabinet behind it comprise lens parts and a microscope among other things. Another cabinet on twirled legs to the right of it is decorated with conspicuous fittings and marquetry. The wood inlaying represents a terrestrial globe and a telescope. According to information from the University Observatory of Vienna, where Rheden lived with his family and worked until long after his retirement, the cupboard can be assumed to have been part of the furniture of this institution that no longer exists. The same motif also adorns wall paneling in an annex of the observatory.[6] Furthermore, this cabinet can also be seen in the background of a self-portrait by Joseph Rheden.[7] Hence, the session for Nähr’s portrait did not take place in his studio but at the University Observatory.

Markus Kristan Karlsplatz and Naschmarkt Scenes Through the Ages

Moriz Nähr's special interest, as well as his preference, was to record changes in city life in photographic form. He usually did this in the immediate vicinity of his apartment in Vienna's 7th district (near the Innere Stadt, the 1st district),[1] but Karlsplatz and the Naschmarkt were also among his commonly frequented areas of activity.

For many reasons, Karlsplatz was an especially magnetic spot for Nähr. One of the main reasons for this may have been that the square – like other districts of Vienna – underwent intense urban development between 1890 and the end of the Habsburg monarchy in 1918. From 1894 to 1900, the River Wien was enclosed, and between 1902 and 1919, the Naschmarkt was relocated in sections from its old location, which extended from the junction of Wiedner Hauptstraße and Karlsplatz, to the banks of the River Wien and the new Wienzeile boulevard created due to the enclosure of the river. With the relocation of the Naschmarkt, the bridging of the River Wien, and the newly built city railway running next to it, there was also a revaluation of the street that ran from the Hofburg to Schönbrunn Palace, thus connecting the emperor’s two residences in Vienna. This ambitious boulevard project was never completed, and to date, only a few magnificent buildings have been constructed – including the three Jugendstil residential buildings that Otto Wagner built for himself on the corner of Köstlergasse in 1898. In the course of the relocation of the Naschmarkt, its trading system was also changed. In contrast to the previous system, the wholesale trade was separated from the retail trade.

Moriz Nähr was always obviously interested in the lively, colorful hustle and bustle of markets. He was thus the first photographer in Vienna to photograph the markets; he would be followed by many more.[2] Nähr developed a very special enthusiasm for the largest market in the city: the Vienna Naschmarkt. Characteristically, he mostly photographed the old Naschmarkt, which existed from 1774 to 1902, and left the new market[3] almost completely unregarded.[4] As numerous photographs prove, the relocation of the Naschmarkt from the junction of Wiedner Hauptstraße and Karlsplatz to the covered River Wien and the Wienzeile attracted Nähr's attention. However a third series of photographs of the Naschmarkt from around 1910 has also survived.[5]

The larger and smaller photo series with Naschmarkt scenes, created over the course of several decades, show different ways of accessing the subject. Essentially Nähr used two design principles, which he occasionally changed within the series: that of the rather free, distanced view, which makes the photographs appear like snapshots,[6] and that of the arranged scene, where he staged and composed the motif as best he could and as far as the "lay actors" allowed it.[7]

Moriz Nähr's final photograph of the Naschmarkt was taken during World War I.[8] After that, his interest in Karlsplatz and the Naschmarkt obviously waned.

Imprint

Editors

Uwe Schögl, Sandra Tretter and Peter Weinhäupl for the Klimt Foundation

Authors

Elisabeth Dutz, Andreas Gruber, Markus Kristan, Astrid Mahler, Alfred Schmidt, Uwe Schögl, Sandra Tretter, Katrin Unterreiner and Peter Weinhäupl

Text and picture editing

Lucy Coatman, Laura Erhold, Liza Fügenschuh

Editing & translation

Wolfgang Astelbauer (†), Karin Astelbauer-Unger, Martina Bauer, Mairi Bunce

Graphic design

dform GmbH